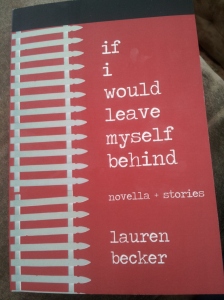

Lauren Becker’s new short story collection, if i would leave myself behind, is being published by Curbside Splendor and should be released by June this year, according to the publisher.

An image of Ms. Becker

I received a review copy of the book, because when I reached out to the publisher to purchase it, they offered to send it if I would write a review. I said sure.

I’ve followed Ms. Becker’s work for a few years, and I’m also a big fan of Corium, the literary magazine she edits. She’s been kind enough to send me editorial notes on my submissions from time to time.

Don’t let the diminutive size of the physical book fool you, or the brevity of the stories, some of which are a slender page, this collection packs an emotional wallop.

All of the main characters in these stories are women, most in severely damaged relationships, some of those relationships are of the woman with herself, and others are disfunctional co-dependent relationships with men. In some cases, there are dying family members too.

willow is a brief internal reflection of a woman suffering with anorexia. There is a Good Willow and a Bad Willow, depending on what she is eating.

In boilerplate, an unnamed woman describes an unpleasant one night stand where she has offered herself up to a man she doesn’t like. She says, “We stared into each other’s eyes for the couple of minutes it took to accomplish his ambivalent satisfaction. Neither of us cared about mine.”

And in tipped a young woman also struggles with body image issues. This paragraph in particular made me laugh: “I was still losing weight. He asked why I was getting skinny. He held my hips when we kissed and put his hands around my belly from behind sometimes when I was brushing my teeth, which I hated. I would like to meet one girl in the world who likes having a guy touch her stomach.”

after the girls of summer describes a horrific relationship with a woman and her abusive boyfriend. The story begins, “When he is sweet, Alex runs his right thumb along Shelly’s left eyebrow. The thick hairs mostly cover the scar where he split her skin for the first time.” And perhaps the most haunting line in that story, “She is the way he made her.”

The 29 stories in this 112 page collection are relentless. They can be read quickly, but when you feel the air squeezed out of your lungs from the horror these women face, day after day, in their cruel lives, with their narcissistic partners, or their disapproving mothers, or dying fathers, it’s a wonder to be able to get through it. But get through it you must, because Ms. Becker’s women characters are compelling in their despair; they are complex in their nonchalant acceptance of their abuse of their bodies and their minds.

Filed under: Blog post, Short Story, Writing | Tagged: Book review, If I Would Leave Myself Behind, Lauren Becker, short story collection, writing | 7 Comments »